To say that the Microsoft Surface has failed to live up to the company’s expectations is an understatement. After poor sales led to a staggering $900 million write-down last summer ( cough, I mean “inventory adjustment”), the second generation of the product has fared only marginally better in terms of sales. But longtime Apple fans know that there’s far more to a product’s merits than sales figures – a fact that’s easy to forget now that the company is dominant in many of the product categories in which it competes – so I was quite perplexed upon reading John Martellaro’s brief blog entry Monday at The Mac Observer, in which he posits that the “complexity” of the Microsoft mobile ecosystem leads to remorseful customers. In short, I think his characterization of the situation is clearly off the mark.

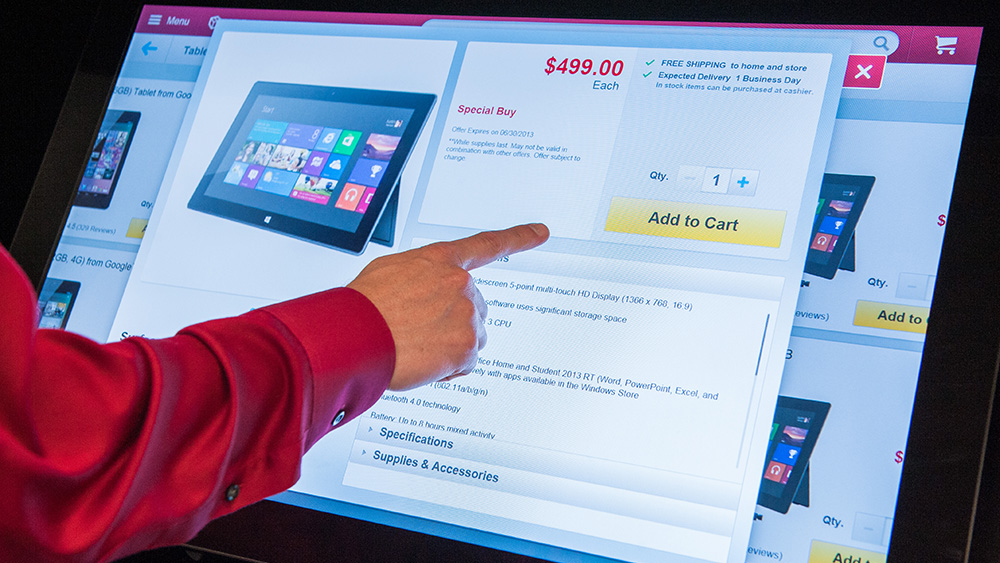

A friend and colleague, Mr. Martellaro consistently approaches his topics with thoughtfulness and fairness, a rarity in today’s link-bait-obsessed technology press. I therefore read his blog entry with eagerness. He tells the tale of a family he and his wife encountered while shopping at Staples: a mother, father, and daughter about to head off to college.

The father had apparently recently purchased an ARM-based Microsoft Surface device (Mr. Martellaro calls it the “Surface RT” but the timing of the event makes it unclear if the product in question was a first-generation Surface RT or its successor, the Surface 2). Unfortunately, the family was forced to return to the store after discovering that the Surface wouldn’t run the daughter’s existing x86 applications.

It’s a clear limitation of any ARM-based product: absent some form of emulation, ARM tablets and phones cannot execute x86 binaries. In the Microsoft world, the company addresses this limitation by offering two separate product lines, the Surface 2 and the Surface Pro 2. The former is ARM-based while the latter has a full-blown x86 Haswell architecture, and is compatible with the complete range of modern desktop applications.

As Mr. Martellaro describes the situation, the family was apparently given incorrect information when purchasing the ARM-based Surface. The daughter was counting on the capability to run her existing desktop applications, and the ARM-based Surface wasn’t going to cut it. Okay, I’m on board with the story up to this point, but here’s where I disagree with Mr. Martellaro.

Right away, I thought about how complexity is the devious manufacturer’s friend. Complexity, clever price points, and the right kind of advertising can convince the uninformed buyer that the solution is painless and inexpensive — when it really isn’t.

I agree, in principle, with Mr. Martellaro’s assessment. But I don’t see how it applies to the Surface, which is a relatively defined and easy-to-understand product category. The problem here isn’t Microsoft’s supposed complexity, it’s a retail salesperson who didn’t know what he or she was talking about.

Of all the products that Microsoft has ever released, the Surface line is relatively straightforward

As mentioned earlier, aside from capacity differences, the Surface line currently consists of two products: Surface 2 and Surface Pro 2 (although you can still pick up the original Surface RT for a discount, as Microsoft attempts to clear unsold inventory). The difference between these products is their architecture, either ARM or Intel (x86). If you want a true tablet that runs touch-focused apps, you go with Surface 2. If you want both a tablet and the ability to run existing Windows apps, you pick up a Surface Pro 2.

Microsoft has been quite clear about this distinction, both with clearly labeled technical specifications for those who know the difference between ARM and Intel, as well as with more mainstream-focused language, such as the Surface Pro 2 is a “tablet that can replace your laptop” and is “compatible with all your favorite Windows software.”

Far from complex, this simple choice is one small area where Microsoft has an advantage over its Cupertino rival. The Surface Pro 2 can’t be compared to an iPad, or other ARM-based tablet. It’s truly a competitor for the MacBook Air and third-party Windows-based Ultrabooks, but with a huge benefit: it functions as a tablet when you want it to, but quickly and easily converts into a full-fledged laptop when you need it, complete with mouse support.

It’s certainly possible that customers armed with incorrect information could mistake the Surface Pro 2’s capabilities for those of the Surface 2, but so, too, could novice Apple customers confuse iOS and OS X, which is exactly what I saw on occasion while working for the company. Whether it was a customer pawing at an iMac screen as if it were a touch screen, or an inappropriately angry lady who stormed into the store one day, screaming at me because she was under the false impression that her new iPad could run the accounting software she’d used on her Mac for years, customers sometimes receive bad information, regardless of how “complex” a company’s product line is perceived to be. Yes, a highly complex product line will facilitate higher incidences of angry customers, but of all the products that Microsoft has ever released, the Surface line is relatively straightforward.

Further, it’s clear to me at this point that Apple is on a path that will someday see the merger of what we now know as iOS and OS X. Likely introduced in phases, it’s unclear if we’ll first see an iPad-like device running a future version of OS X, or a MacBook Air-like device running a future version of iOS, but I’m betting we’ll get at least one in the next few product cycles. In either case, such a move would introduce the exact same scenario that Mr. Martellaro now labels as problematic for Microsoft, but I doubt that many will view this move as an unnecessary increase in the complexity of Apple’s product line.

“Complexity” isn’t the issue here, just bad information

New technologies often require customers to abandon their existing platforms. Although Microsoft has traditionally been much better about backwards compatibility than Apple, the move to mobile computing is the introduction of a new world. Neither Mr. Martellaro nor myself bemoaned the introduction of iOS as unnecessary complexity, and we expected Apple’s customers to understand that their OS X software wouldn’t run on Apple’s new devices (which is not as clear-cut to novices as it seems, as Apple now markets software for both iOS and OS X as simply “apps”).

Mr. Martellaro also notes that “any kind of good solution to this family’s problem is going to cost serious money,” but I fail to see how that’s a knock against Microsoft or the company’s “ecosphere.” The daughter in this tale had an old Windows-based laptop that was in need of replacement. Buying a new computing device is going to cost anyone money, regardless of whether the “ecosphere” is Apple’s, Microsoft’s, or anyone else’s.

Flipping the situation for a moment, if the daughter had an old 2006 MacBook and wanted to buy a new Apple device that could run her existing apps, her cheapest option would be a $1,000 11-inch MacBook Air. There are many Windows-based devices, including the Surface Pro 2, that are at or below that price point.

If a customer wants a Windows laptop, they should buy a Windows laptop. If they want a Windows tablet, they need only ask themselves if they want to preserve compatibility with existing desktop apps. The answer to that question will direct their choice, and the same calculation applies to Apple.

Microsoft’s Surface is certainly far from perfect, and customers may still feel “buyer’s remorse” based on their personal experience with the device. But “complexity” isn’t the issue here. The family that Mr. Martellaro encountered had simply been fed bad information, and that’s something that can happen to any consumer, in any store, with any company’s product.